Robert Sagar

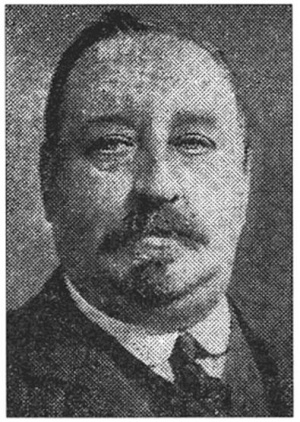

Robert Sagar (c. 1852-1924).

City of London CID officer (afterwards inspector) who later described the surveillance of a Ripper suspect in Butchers' Row, Aldgate. He also represented the City of London police in nightly meetings with the Metropolitan Police during the period of the murders.

The Whitechapel Murders

According to the press reports of his retirement, Robert Sagar represented the City of London Police at nightly meetings with the detective heads of the Metropolitan Police at Leman Street Police Station during the period of the murders[1][2][3][4][5].

Sagar related another anecdote about the investigation at the time of his retirement:"The disguise of a laborer was used, too, when Mr. Sagar made investigations into the notorious "Jack the Ripper" murders. So effectual was his disguise that he was actually tracked himself by two police-officers, who thought they had reason to regard him as a suspicious character."[3]

Regarding the murders and the identity of the killer, several of Sagar's opinions are quoted in the reports of his retirement. Obviously in some respects his recollections are at variance with the contemporary evidence:

- Just before the discovery of the body of Catherine Eddowes (called Kelly in the reports) in Mitre Square a police officer met a man of Jewish appearance coming out of the court[2][3][4]. In one report the officer is said to have been a constable[3], and in the other two is said to have discovered the body immediately afterwards. The Jewish man is described as "well-known" in one report[2], and "well dressed" in another[4].

- Two of the reports refer to "retreating footsteps" then being pursued as far as the King's Block in the model dwellings in Stoney Lane (i.e. the Artizans' Dwellings)[2][4].

- Mention is made of the writing on the wall above the victim's apron, quoted as either "The Jewes are not the people that will be blamed for nothing"[1][2] or "The Jews shall not be blamed for this"[3][4]. In two reports this is said to have been under the stairs "in a common lodging house in Dorset Street."[1][2]

- A suspect is referred to. Although it is stated that the police could prove nothing, three of the reports express moral certainty as to the suspect's guilt ("a man, who, without doubt, was the murderer"[1], "I feel sure we knew the man"[2], "The police are satisfied as to the identity of the man"[4]). According to two of the reports this was a man who worked in Butchers' Row, Aldgate[3][4] - as a butcher according to one of them[4]. (A report published after Sagar's death says he was "employed" at Butchers' Row, but this may just be a rewording of the earlier articles[6].) The man is variously described as insane[3] or partly insane[4], and said to have been watched carefully by the police[3]. Three of the reports say that he was put into a lunatic asylum[1][2][3] (a private asylum according to one[3]) and that the murders then came to an end. The fourth says that it is believed that he made his way to Australia and died there, "but what became of him we don't know."[4]

It has been suggested that this may be the same suspect mentioned in the memoirs of Sagar's colleague Henry Cox. No contemporary reference to the observation of this suspect is known, though evidence in an unrelated case suggests that Sagar may have been carrying out surveillance in Aldgate in April 1889[7]. It has also been suggested that there may be a connection with a raid on a gaming house known as the Alliance Club in Bull Inn Yard, Aldgate, in December 1890. The raid followed observation of the premises, which lay off Aldgate High Street directly opposite to Butchers' Row[8].

There is a surviving report from September 1889 by Sagar concerning an anonymous letter alleging that a murder had taken place in Great Prescot Street shortly before the discovery of the Pinchin Street Murder. He had shown the letter to Detective Inspector Reid of H Division, who told him that the writer was known to him and was insane[9].

Biography

Robert Sagar was born in either 1852 or early 1853 at Simonstone, Lancashire, where Sagars had lived for centuries[10]. He was the son of Robert Sagar, a farmer, (born c. 1821 in Simonstone) and his wife Sarah (born c. 1831 in Whalley). He was living with his parents at New House, Simonstone, at the dates of the 1861 and 1871 censuses[11]. He was educated at Whalley Grammar School[1][2][3] and acted as assistant to Dr Badely of Whalley[12].

In October 1871 he enrolled as a medical student at St Bartholomew's Hospital in the City of London, where he remained until December 1878[13] (though a later press report said he spent only five years there[4]).

While a student, he lodged in the house of a City of London detective named Potts in Bartholomew Close[14]. As a result he seems to have taken up detective work as a hobby, according to his later account appearing in many prosecutions in the City Police Courts and at the Old Bailey, and helping to arrest over a hundred offenders[15]. He is said to have attracted the favourable attention of the City of London Police Commissioner, Sir James Fraser, who encouraged him to join the force, with the result that he gave up his studies in order to do so (although, according to his application form, his studies had ended nearly a year before he became a police officer)[1][2][3][4].

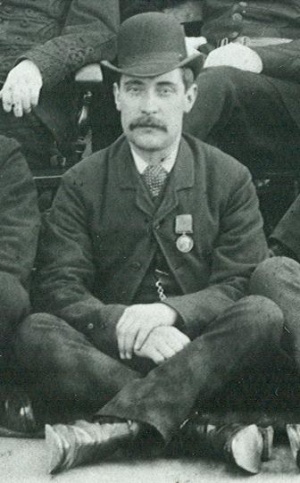

Sagar was initially evaluated as medically unfit, because it was supposed that he had a varicose vein in one leg. In fact this was an injury he had sustained while pursuing a thief as an amateur in company with Detective James Egan, and he later passed the medical examination[1]. He joined the force as an ordinary constable, but a note in his personnel file recorded that he was "not to be clothed" as he was to be attached to the Detective Office[13], and he was later said to be the only officer of the City of London Police who had never worn uniform[1][2][3][4]. Because of his medical background, Sagar was nicknamed "the Doctor" by his colleagues[3][4][16].

Major Henry Smith, the Commissioner of the City of London Police between 1890 and 1901, told the story in his memoirs of how Sagar had "abandoned ... the scalpel for the truncheon," and said that he had made a wise choice, "for a better or more intelligent officer than Robert Sagar I never had under my command." [17]

According to reports of his retirement, the first case he investigated, during his probationary period, was one of fraud, which other officers had failed to solve[1][2][3]. The culprit, William Henry Walter (called "William Waiter" in the only one of these reports to name him), was tried in March 1880 and sentenced to 20 years' penal servitude[18].

Robert Sagar's activities in several dozen cases over the course of his career are recorded in newspaper reports, the Old Bailey Proceedings and the surviving City of London CID records at the London Metropolitan Archives. They concern a wide range of offences, including pickpocketing, confidence tricks and frauds, the operation of an illegal still, the breaking of the Sunday licensing laws, blasphemy, thefts from warehouses and elsewhere, the desertion of a wife, coining and the forging of banknotes, bonds and begging letters, and bank robbery. He was also involved in many raids on illegal gaming houses in the City. Among the prominent cases that he recalled at the time of his retirement were those of Mrs Florence Ethel Osborne, who was convicted of theft and perjury in 1892 after she stole her friend's pearls and then brought an action for slander against her and her husband when they accused her of the theft[19], the father and son Solomon and William Barmash, who were convicted of forgery in 1893 and again in 1902, after which Solomon committed suicide in prison[20], the forger Johann Schmidt who worked for them[21], Charles Hamlyn alias Henry Miller, convicted in 1897 of large-scale fraud through his "Perfection System of Investment"[22], Henry Devenport and others, convicted of forging five-pound notes in 1902[23], and Anthony Stanley Rowe, a mining engineer, who was convicted of forgery and fraud against the Great Fingall Consolidated Limited in 1903[24].

At about the same time he joined the police force, Robert Sagar was married to Clara Watling in Shoreditch[25], where Clara had been born.

Robert and Clara had three children[26]:

- Robert Henry, b. 1880

- Sarah Jane, b. 1882

- Cecil William, b. 1884

At the date of the 1881 census, the family was living at 10 Bridgewater Square in the City of London[27].

Sagar took part in an unusual investigation following the insertion of an "obscene and fictitious line" by an employee of the Times in a report of a speech made by the Home Secretary, Sir William Harcourt, in January 1882. Sagar and his colleague [John] Davidson were "instructed to mix with the compositors when they go out for refreshment at night, and in the morning with a view to glean something from their conversation."[28]

In February 1884 he was advanced to the rank of Detective Constable[13].

In December 1887 he was granted 8 days' leave to attend his mother's funeral[13][29].

On 6 December 1888 he was advanced to the rank of Sergeant[13]. According to one of the reports of his retirement, this promotion was "of an honorary character, and it was conferred by the Commissioner in recognition of special services rendered."[1] His advance to the rank of Detective Sergeant followed on 8 June 1889. On 13 November 1890 he was made a Detective Inspector[13], becoming a first-class Inspector three years later[1].

In October 1890 he was involved in the investigation of George Johnson and John Phillips, who were convicted of attempting to defraud the banking firm of Drexel, Morgan and Co., a case in which Henry Cox was also involved. At his retirement, Sagar described Johnson as the smartest forger of banknotes he had known, and told the story of how he had been tracked down to a house in Bethnal Green, where Sagar had discovered a bundle of forged banknotes[2][3]. However, his memory seems to have been at fault, as Johnson and Phillips were convicted of forging letters of credit, not banknotes, and it was at a house in Twickenham that Johnson was arrested[30].

By the date of the 1891 census he was living with his wife and children at 13 Rose Alley, off Bishopsgate Street[31]. They were still living there in 1901[32]. A report of his retirement mentioned his leaving "the comfortable quarters in Rose-alley, Bishopsgate, which he has occupied for so long"[2]. Presumably these were in the block of accommodation for married police officers which had been built there in 1876[33].

He retired after 25 years' service on 5 January 1905[13]. His retirement was reported by the City Press[1], the Morning Leader[3], the Daily News[2] and another unidentified London newspaper[4], and by others which copied them. A comparison of these four reports can be seen here.

After his retirement he moved to Preston Park, near Brighton, in Sussex. In February 1909 he was living at "Brooklands," 4 Surrenden Road, Preston Park.[34] He was living at Preston with his wife and younger children at the date of the 1911 census. His wife died the following year at the age of 54[35].

He died on 30 November 1924 at his home, "Homeleigh," South Road, Preston Park, at the age of 72[36], and was buried at Brighton and Preston Cemetery. His health was reported to have broken down following a fall in the street[6]. His death was reported by several newspapers, and some of the details published at the time of his retirement were repeated[6][16][37].

References

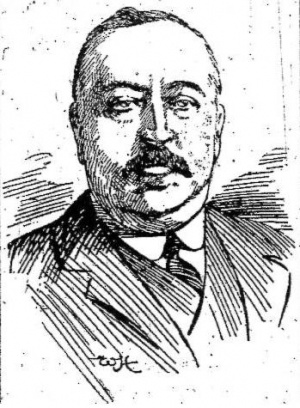

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 City Press, 7 January 1905, which includes a photograph of Sagar. Parts of this report were reprinted in the Star, 7 January 1905, and the News of the World, 8 January 1905, the Star including a sketch based on the photograph.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Daily News, 9 January 1905. This report was reprinted with only small changes in the Mercury, 14 January 1905.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 Morning Leader, 9 January 1905. Part of this report was quoted in an article by Justin Atholl, published in Reynolds News, 15 September 1946, which was the first reference to Sagar's suspect to be discovered.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Seattle Daily Times, 4 February 1905. The same report appeared, with only small differences, in the St Paul Globe, 6 February 1905. The English source of this version has not been traced, but judging by the similarity of the wording it was probably also the basis of a brief report of Sagar's retirement which appeared in the Sunday Chronicle on 8 January 1905, and of another in the Daily Mail of 9 January (which was reprinted in the Police Review on 13 January 1905). The statement about Australia also appeared in a report published in the Gloucester Citizen on 9 January 1905, attributed to a recent interview with Sagar. The original report probably included more material than was reprinted by the Seattle Daily Times, whose final section contains nothing relevant to its title, "Has a Charmed Life."

- ↑ According to the Seattle Daily Times report, he was "the chief officer appointed to confer with the metropolitan police" about the murders. But it seems unlikely that the City Police would appoint a detective constable to confer with senior Scotland Yard detectives. On 27 October 1888, Inspector James McWilliam, the head of the City Detective Department, noted that "Chief Inspector Swanson and I meet daily and confer on the subject" (Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, p. 202 (2000)).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Brighton and Hove Herald, 6 December 1924.

- ↑ Times, 3 April 1889. Detective Sergeant Pentin had followed a suspicious character who entered 5 Duke Street, and was able to "communicate with" Sagar, who helped him to search the premises and arrest the man.

- ↑ Scott Nelson, "Inspector Robert Sagar and the City of London Police Raid on the Bull Inn Yard, Aldgate," Ripperologist 103, June 2009.

- ↑ Report dated 7 September 1889 and letter number 373, among the City of London Police correspondence at the London Metropolitan Archives (CLA/048/CS/02/373), reproduced in Stewart Evans and Donald Rumbelow, Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates, p. 211 (2006).

- ↑ A Robert Sagar bought property there as early as the 1560s (Victoria County History, Lancashire, vol. 6, pp. 496-503 (1911); Text at British History Online).

- ↑ RG 9/3076, RG 10/4154.

- ↑ Paul Begg, Martin Fido and Keith Skinner, The Complete Jack the Ripper A to Z, pp. 451-453 (2010).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Personnel file, in box CLA/048/AD/01/651, London Metropolitan Archives.

- ↑ William Potts and his family were living at 47 Bartholomew Close at the date of the 1881 census (RG 11/374, f. 92). Although the reports of Sagar's retirement describe Potts as "a celebrated City detective," "a first edition of Sherlock Holmes" and in one instance as a sergeant, in fact he was only a detective constable at that time. Potts is mentioned in press reports between 1862 and 1884, and presumably retired soon after that.

- ↑ He gave evidence at three Old Bailey trials in January, February and March 1879, concerning cases in which he had assisted police officers (Old Bailey Proceedings, 13 January, 10 February and 31 March 1879).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 City Press, 6 December 1924.

- ↑ Sir Henry Smith, From Constable to Commissioner, pp. 112, 113 (1910).

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 22 March 1880.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 7 March 1892; Times, 9 March 1892.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 1 May 1893, 15 December 1902 and 27 April 1903.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 15 December 1902 and 27 April 1903.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 26 July 1897.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 2 June 1902.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 14 December 1903.

- ↑ Marriage registered in March quarter 1880 (Shoreditch, 1c 225).

- ↑ Census and civil registration records.

- ↑ RG 11/372, f. 23v.

- ↑ London Metropolitan Archives, CLA/048/AD/11/8. For further details of the incident see this Wikipedia article.

- ↑ The death of Sarah Sagar, aged 58, was registered at Burnley in December quarter 1887 (8e 195). Burnley registration district included Simonstone.

- ↑ Old Bailey Proceedings, 24 November 1890.

- ↑ RG 12/235, f. 160.

- ↑ RG 13/262, f. 126v.

- ↑ Sir Walter Besant, London in the Nineteenth Century, p. 108 (1909) (Text at the Internet Archive).

- ↑ Will, dated 9 February 1909, and proved at Lewes 16 December 1924.

- ↑ Index entry for the death of Clara Sagar (September quarter 1912, Steyning, 2b 295).

- ↑ Death certificate (December quarter 1924, Steyning, 2b 299). The cause of death was "1 Arterial Sclerosis. 2 Static Bronchitis. Syncope."

- ↑ Brighton Gazette, 6 December 1924; Southern Weekly News, 6 December 1924; Burnley News, 17 December 1924, quoted by Paul Begg, Martin Fido and Keith Skinner, The Complete Jack the Ripper A to Z, p. 452 (2010).