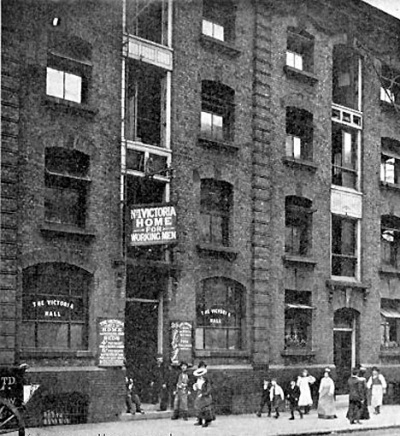

Victoria Working Men's Home

Demolished.

Large lodging house at 39-41 Commercial Street, situated on the south-western corner with Wentworth Street. Registered in November 1887, it was run at that time by Augustus Wilkie of 77 Whitechapel Road and was originally licensed to house 370 male lodgers, though expansion allowed for an increase in occupants within a short time. In 1888, a press report outlined its intentions and its initial success:

"It was with a view to ameliorate the condition of the poor that Lord Radstock and other gentlemen, with a purely philanthropic motive, acquired two years since a warehouse of four floors in Commercial-street, at the corner of Wentworth-street, and converted it into a model lodging-house. The success of the venture led to the acquisition of the adjoining premises, and the number of beds now provided is 500. In every respect this lodging-house - the only one of its sort in London - deserves to be imitated. First, its charges are low - viz., 4d for a single bed, or 2s per week; and 6d for a "cabin," or 3s per week. Each bed has two blankets, two sheets, and a quilt; the bedstead is of iron, and a kind of shield at the head affords a certain degree of privacy. The floor space is partitioned into rooms, containing each ten or a dozen beds; whilst in the "cabins" there is only one. A "casual" ward for the reception of newcomers has lately been added, and probationers are transferred thence to floors above. Many of the lodgers are regulars, but some are birds of passage purely. The lavatory, ventilating, and sanitary arrangements are on an enlightened scale. In the common kitchen food may be cooked at the great fire, or obtained at low charges at the bar, a dinner with vegetables for fourpence, or a bowl of soup for a penny. No known bad characters are admitted. Tickets for beds are issued from five p.m. until 12.30 midnight, and after that hour if a man wants to get in he must have a pass. It is by these rules, especially, and by the exclusion of women, that the Victoria Home is so greatly to be preferred to the most modern and "improved" of the lodging-houses which are strictly commercial undertakings."[1]

The rules of the home were such as to deter 'bad characters':

1) No person in a state of intoxication will be on any account admitted.

2) No swearing or obscene language will be tolerated; order and decorum are insisted in the kitchens; silence in the bedrooms.

3) No person will be admitted after one o'clock a.m. without a special pass.

4) Any lodger interfering with the comfort of others is at once ejected.

5) Lodgers who are fortunate enough to possess extra clothing or other personal effects, can leave them in charge of the deputy, who will give a receipt for the same.

6) Baths, warm or cold, can be had in the house. For a warm bath, the charge of one penny is made.[2]

Witness George Hutchinson, who saw Mary Jane Kelly with a man in Commercial Street on the morning of her murder, was at that time a resident of the Victoria Home[3].

Several years later, James Sadler, lover of Frances Coles who was originally suspected of her murder, stated that he had gone to the Victoria home at 8.30pm, 11th February 1891, before going across the road to the Princess Alice where he met Coles[4]. He was also recorded as staying there in April 1891. By this time, it was run by Charles William Mowl and housed nearly 500 men.[5]

The Victoria Working Men's Home was totally destroyed during an air raid in the Second World War[6] and the site remained empty for many years before being redeveloped as part of the New Holland Estate in the late 1960s.[7]

References

- ↑ Daily Telegraph, 22nd September 1888

- ↑ Later Leaves, Montague Williams, 1891

- ↑ Hutchinson's statement, 12th November 1888, MEPO 3/140, ff.227-9

- ↑ Statement by James Sadler, 14th February 1891, MEPO 3/140, ff.97-108

- ↑ Census reports 1891

- ↑ The London County Council Bomb Damage Maps, 1939-45, Ed. Anne Saunders (London Topographical Society 2005)

- ↑ Tyne Street redevelopment - plans 1964-71 (London Metropolitan Archives)